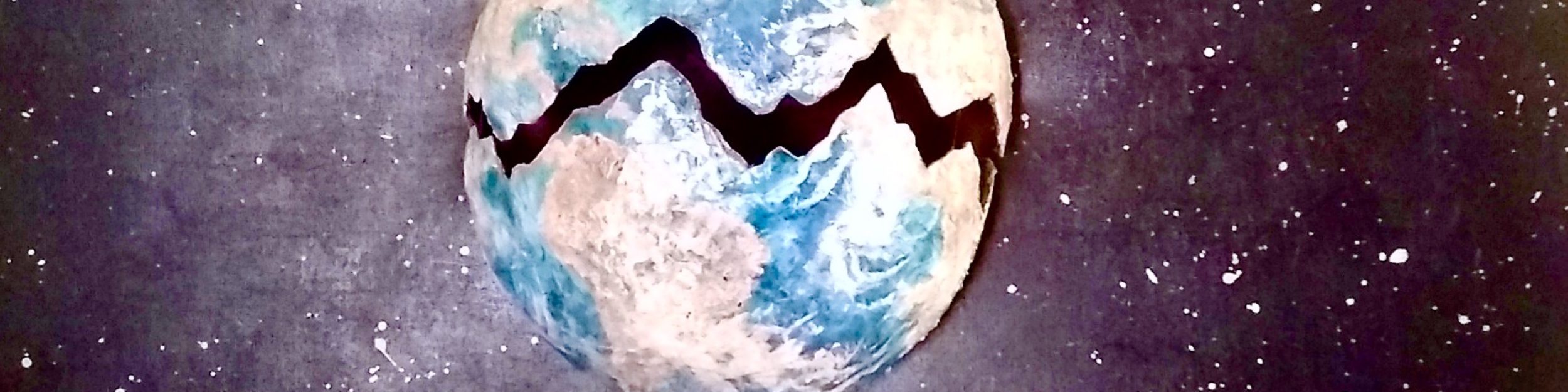

AN IMPENDING CALAMITY

PROLOGUE

YAMAL PENINSULA

REMOTE REGION OF SIBERIA

FAR NORTH RUSSIA

JUNE 21, 2016

SURVIVAL FOR MORE THAN A FEW MINUTES WASN’T LIKELY, BUT THE THREE SCIENTISTS DIDN’T KNOW THAT. They stood next to a mound of sodden grass about a foot-high and eight feet in diameter. Kyle Hardin’s parka hood was blown back by the fierce wind, exposing shoulder length hair, chiseled features, a broad forehead and blunt chin. A GO GREEN pin was attached to his collar. He and David Harrison, the grad student he’d brought along, were Americans. Anatoly Volkov, their Russian colleague, shifted the heavy backpack slung over his left shoulder and moved closer to the edge of the mound.

The others watched as he took the long-handled shovel he carried and jabbed it into the mushy earth.

Volkov was brawny and muscular, but the shovel didn’t budge. His knee-high rubber boots sank into the ground as he pushed. Nothing happened. Volkov leaned down and pushed harder. A plume of gas spat up from the hole he’d dug, followed immediately by an enormous explosion. Red and yellow elliptical flames shot into the air.

The scientists were flung skyward with a billowing plume of thick black smoke. Chunks of dirt and rock flew out of the epicenter simultaneously. The accompanying boom was so loud that it startled reindeer herders in a nearby camp.

A ferocious gust of wind swept across the plain, blowing the plume of smoke out over the marshy landscape. When the air cleared, the mound was gone. In its place there was a massive hole, about 35 feet deep and a dozen feet wide, surrounded by rocks and debris scattered mostly around the rim. Kyle and David lay sprawled on the ground, covered in dirt, bits of rock and mutilated blades of grass.

Most of Voltov’s body was submerged in the hole. He hung onto the edge desperately, digging his fingers into the grass and dirt. Kyle dragged himself to his knees. Small nicks covered his face and left hand. He shook debris from his shoulders and wiped away blood using the torn sleeve of his parka. As he stood, he lost his balance, dizzy with ears ringing. He stumbled over and sized up Anatoly’s situation. He looked down. The hole was about three and a half stories deep. It was almost certain death if Voltov fell. David lifted his head, but he was too stunned to get up.

Kyle lay down in the morass and grasped the Russian’s wrists. Voltov was heavy. Too heavy. His substantial bulk made it hard for Kyle to hang onto him. His grip slipped.

“Let me go,” Anatoly rasped. “Or you fall with me.”

“No way.” Kyle wasn’t about to give up even though it seemed like a lost cause. “See if you can let go of your backpack.”

Anatoly lifted one hand, using it to shrug the bag off his shoulder. That reduced his grip on the grass, and he sank farther into the abyss. Kyle started to slide toward the hole. He jabbed his feet into the rubble, but continued to slip.

Voltov looked up at him. “Let go,” he repeated.

Kyle didn’t respond. He gripped Voltov’s wrist tighter as the Russian tried to pull it free.

Suddenly Kyle stopped sliding as a large rock wedged in front of his left boot. With the backpack gone and a lighter load, he pulled the Russian over the edge inch by inch, through the debris and onto the grass.

Anatoly was covered with fragments of stone, but unhurt apart from scratches on his face and singed hair. He lifted himself up and wiped bits of dirt off his ruined slicker. Kyle got to his feet, took a handkerchief from his pocket and swabbed the gash above his right eye. The two of them helped David stand up. He had even more cuts on his face than they did. His scorched parka had a ragged slit from top to bottom. He covered his ears with both hands, trying to stop the incessant buzzing. Since he was still shaky, they took his arms, and all three walked back to the edge of the massive hole. Beyond it a vast expanse of flat tundra extended to distant jagged mountains, their tops streaked with retreating glaciers. Around it the thawing permafrost was covered in marshes, lakes, swampy bogs and streams.

They stood there, staring down into the chasm and shook their heads.

“Must have been methane,” Kyle said. “If that ferocious wind hadn’t blown it away from us, we would all be dead.” And methane might end up wiping out civilization anyway, he thought.

ONE MONTH LATER

REMOTE REGION OF SIBERIA

BURIAL SITE

JULY 21, 2016

PETRAKO AND EDEYNE SERAKONE CLUTCHED THE HANDS OF THEIR TWO REMAINING CHILDREN as the crudely-made wooden coffin was lowered partway into the mushy Siberian ground. Natena, their eldest son, had been only 12 years old when he died. He would never follow in his father’s footsteps as a reindeer herder.

Edeyne couldn’t bear the sight of the brightly flowered scarves and hats trimmed in multi-colored braid, the hallmarks of their nomadic tribe, worn by neighbors who came to mourn with them. So much color amidst so much sadness. She stared at the ground.

At her feet shaggy grasses mixed with occasional mounds of dirt. Other rough-hewn coffins lay half-buried in the soggy ground next to handmade wood crosses. Some were on stands above ground. Overhead a wan sky was lightly dusted with shifting clouds. It had turned colder, but the permafrost was still thawing.

Her husband Petrako, his skin weather-beaten from a life outdoors, pushed the tilted cross next to the small grave farther into the ground. The sodden earth couldn’t hold it upright. With lingering glances, all but Petrako slowly trudged away.

He looked down at the coffin and sighed. A week ago his son had awakened at midnight and vomited until his stomach hurt so much that he cried. Natena was a boy who never cried. Then he developed unrelenting fever and bloody diarrhea. The family rushed him to the nearest hospital. Helpless, they watched him slip away.

Petrako had expected Natena to herd reindeer as his father and grandfather had, but he had begun to worry. Their animals were hungry since there wasn’t enough pasture now. The snow melted sooner and faster than ever. In spring the tired reindeer struggled to pull sledges. They couldn’t cross the frozen river in November to set up camp in the southern forests. The ice was too thin until late December. Petrako had noticed the glaciers looked smaller every year, and the ground was increasingly soggy. A month ago, he had heard a loud bang which he learned was from an explosion that left a gigantic hole in the ground. He was told that some American scientists had been involved. Seven days later he found that forecasters recorded an unprecedented temperature of 35 degrees (95 degrees Fahrenheit).

That week the family ate cooked reindeer for dinner. They didn’t know the meat was contaminated most likely by a reindeer infected with anthrax 75 years ago. Bacteria in the corpse, preserved in the permafrost all those years, were still lethal when exposed today.

Climate Crisis Blog